The following detailed history of the Tunica is taken from a paper entitled “A Promise from the Sun: The Tunica-Biloxi Indians of Louisiana” by John Barbry, Director of Development & Programming for the Tunica-Biloxi Language & Culture Revitalization Program. As a historian and archivist, Barbry has extensively researched the history of his tribe. More information about John Barbry may be found here.

Tunica in the 18th Century

Tunica-Biloxi history is closely intertwined with the history of Louisiana. French and Spanish colonial governments depended on the Tunica for trade, diplomacy with other tribes, and as a barrier against British encroachment. As the southernmost Indian nation to oppose the English, the Tunica cultivated a relationship with France as early as 1699. Hatred of the English-inspired and English-armed Chickasaw slave traders brought the French and Tunica together and prompted the Tunica to move their village from the Yazoo River basin halfway to New Orleans.

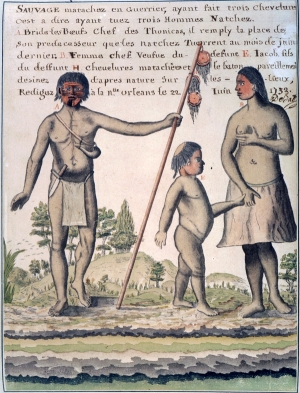

Water color painting by French artist Alexandre de Batz depicting a Tunica chief painted for war, 1732.

By establishing themselves opposite the juncture of the Red and Mississippi rivers, the Tunica afforded their community a commanding position on trade routes between the two river valleys and New Orleans. The Grand Tunica Village provided a buffer between the French and the Natchez and served later as French headquarters during the long Natchez wars. As participants in the Pontiac rebellion, the Tunica concluded their alliance with France by attacking an English settlement party in 1764, shortly after France had lost its North American colonies.

Retaliation by Britain against the Tunica and allied tribes made the transfer of loyalty from France to Spain a convenient one. The Tunica favored the Spanish for their promise to honor previous agreements established between France and the Indian nations. When Spain sided with the colonists in the American Revolution in the fall of 1779, Tunica warriors fought side by side with Spanish Governor Bernardo de Galvez, attacking British posts at Manchac and Baton Rouge. Following the battles, Galvez invited the Tunica and their Ofo and Biloxi allies to settle on the Avoyelles Prairie, the area surrounding present-day Marksville, Louisiana.

Tunica in the 19th Century

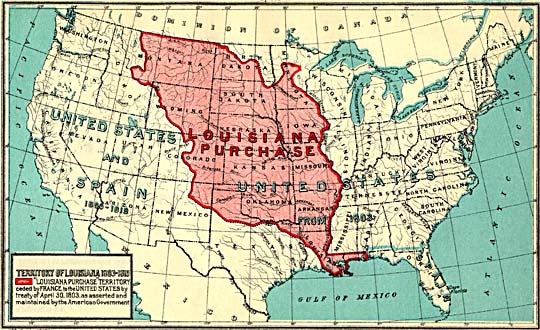

After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the United States committed itself to a policy of protecting Indian land and rights, but in reality it disregarded the smaller Louisiana tribes in order to appease discontent among former French and Spanish colonists. Once afforded respect and protection by Spain as a sovereign nation, the Tunica lost their land to French settlers who registered the land as “unoccupied” so that they could make fraudulent claims to it. John Sibley’s 1806 report provided the United States government with questionable data, which dismissed most Louisiana tribes as insignificant remnants. Suffering the fate of other southern tribes, the Tunica in small numbers on small tracts of land were of no concern to the federal government and posed little obstacle to the expanding frontier. The government, therefore, felt no pressure to recognize them or formally deal with them by treaties. The eagerness of the United States to recoup the cost of Louisiana coupled with its ignorance and disregard for the smaller tribes worked against the Tunica. Thus, the Tunica escaped the removal policy of the 1830’s and 40’s and kept their village on the Avoyelles prairie.

After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the United States committed itself to a policy of protecting Indian land and rights, but in reality it disregarded the smaller Louisiana tribes in order to appease discontent among former French and Spanish colonists. Once afforded respect and protection by Spain as a sovereign nation, the Tunica lost their land to French settlers who registered the land as “unoccupied” so that they could make fraudulent claims to it. John Sibley’s 1806 report provided the United States government with questionable data, which dismissed most Louisiana tribes as insignificant remnants. Suffering the fate of other southern tribes, the Tunica in small numbers on small tracts of land were of no concern to the federal government and posed little obstacle to the expanding frontier. The government, therefore, felt no pressure to recognize them or formally deal with them by treaties. The eagerness of the United States to recoup the cost of Louisiana coupled with its ignorance and disregard for the smaller tribes worked against the Tunica. Thus, the Tunica escaped the removal policy of the 1830’s and 40’s and kept their village on the Avoyelles prairie.

An opportunity for the Tunica to reclaim their land arose in 1844 when Celestin Moreau charged five of the tribe’s old women with trespassing. The case of Moreau vs. Valentin, et. al, brought the brunt of court costs to Moreau and allowed the Tunica a fair hearing. There was enough evidence for the court to rule in the Tunica’s favor, removing Moreau from the land and awarding monetary damages. However, the case dragged on and in 1848 an arrangement was made giving Moreau clear title to 586 acres and leaving the Tunica with a 132-acre tract which to this day is known as the “Indian Reservation.” As a result, the United States government had no involvement in the establishment of the reservation

An opportunity for the Tunica to reclaim their land arose in 1844 when Celestin Moreau charged five of the tribe’s old women with trespassing. The case of Moreau vs. Valentin, et. al, brought the brunt of court costs to Moreau and allowed the Tunica a fair hearing. There was enough evidence for the court to rule in the Tunica’s favor, removing Moreau from the land and awarding monetary damages. However, the case dragged on and in 1848 an arrangement was made giving Moreau clear title to 586 acres and leaving the Tunica with a 132-acre tract which to this day is known as the “Indian Reservation.” As a result, the United States government had no involvement in the establishment of the reservation

Tunica in the 20th Century

As the Tunica village entered a new century its economy continued much as it had before. The land yielded game for hunting and fishing and was farmed mostly for subsistence. Some cotton, garden crops, and chickens provided a small income. Indians also harvested pecans in abundance on the reservation, and brought a small profit. Primarily for personal consumption, corn furnished a staple for the tribe and became an important part of the traditional culture through celebrations and tribal rituals. Beautiful split-cane baskets woven by the women of the village became well known in the surrounding communities and were sold at grocery stores and along the road. Some families farmed land outside the reservation, earning money to build houses and purchase items unavailable on the reservation.

The plunge in the cotton market in 1919 made sharecropping an uncertain prospect and pushed the Tunica and other rural inhabitants toward wage-earning jobs. One major source of income was the lumber industry, which had been important to central Louisiana economy since the coming of the railroad in the 1880’s. When sawmills started to close and move to southwest Louisiana and Texas, Tunica families followed in search of work. The departure of families from this area was a new experience for the community, which marked an era of decline in traditional Indian culture.

Beginning with tribal leader Sesostrie Youchigant in 1911, the Tunica village maintained a rather formal system of electing their chief. It was at this time that the tribe began recording the elections in the parish courthouse. Youchigant resigned in 1921, making way for the election of Ernest Pierite as chief and Eli Barbry, Youchigant’s half brother, as subchief. Meanwhile, living conditions in rural Louisiana worsened.

As early as 1922, Barbry started making inquiries to the Department of the Interior concerning ownership of their land. Barbry’s political activism moved somewhat beyond his role as sub-chief as he attempted the unification of the Tunica with “the Biloxi tribe” (meaning the Indian Creek settlement) and the Jena Choctaw. His pan-tribal efforts continued with the Coushatta of Allen Parish, in 1924, and the Chitimacha of St. Mary parish in 1925. Notarized documents naming Barbry chief of these groups stated that the tribes were coming together “for the purpose of union of the people of our race, to promote our welfare and to secure for ourselves and our descendant’s educational and religious training, to the end of our becoming better citizens of this American Nation…” All of these documents were signed by the various tribes except for the Chitimacha who refused to join the alliance and sought their own aid.

Allotment and forced assimilation continued to be hallmarks of United States Indian Policy until 1934, when President Roosevelt’s new Commissioner of Indian Affairs, John Collier, began a comparatively enlightened “Indian New Deal.” Collier thought Indian culture should be preserved as it provided an example of healthy organic societies in which people were motivated by shared obligations. By authoring the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, Collier brought the allotment program to an end, extended indefinitely the period of trusteeship over Indian land, established the basis for democratic tribal governments, and confirmed the rights of tribes to greater control over their destinies.

The Tunica, under pressure in the Depression Era, had no choice but to seek aid and recognition from the federal government. Community resources were mobilized and money was raised from the village and its extension in Texas to send tribal leaders to meet with BIA officials. In September, 1938 Chief Barbry, Sam Barbry, Clarence Jackson, and Subchief Horace Pierite, Sr. drove to Washington in a Model T Ford accompanied by a local parish official, Joseph Vilmarrette. The members of the delegation promptly identified themselves by separate tribal affiliation. They met with BIA officials to discuss their situation and explain the problem of the diminishing Marksville land and sought to press a claim for lost lands. They wanted aid to improve economic conditions and educational needs so that the Texas families could return.

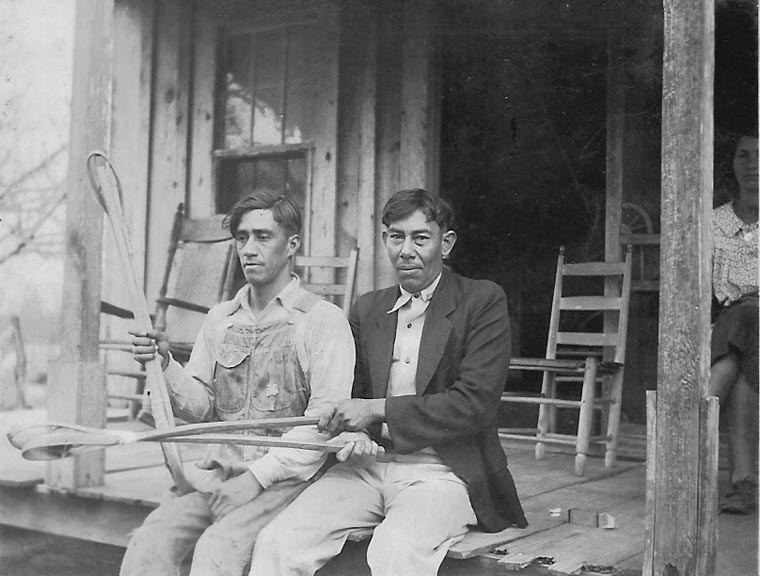

Merlin Pierite and Joseph Pierite holding stickball racquets, ca. 1930.

(Photo: Frank Speck, Gregory Collection, Northwestern State University.)

As a result of Eli Barbry’s efforts and the recommendations of anthropologist, Frank Speck, and Ruth Underhill of the BIA’s education department, visited the village a month after the delegation’s visit. Citing discrimination, Ms. Underhill reported that the young people were anxious to move to Texas, where economic and educational opportunities were better, and noted that much of the migration had already occurred. The government maintained their policy of disregard and neglect toward the Tunica-Biloxi. Other Indians faced the same problem, as members of unrecognized bands or tribes were also excluded from the benefits of the Reorganization Act. Pressure from the Tunica-Biloxi and their political constituency in Congress motivated the Indian Bureau to at least acknowledge the tribe’s existence and to investigate their claims. Twentieth century documentation of the Tunica-Biloxi was finally updated by the government and provided the first step whereby federal recognition was accomplished.

The death of Sesostrie Youchigant in the 1940’s marked the decline in use of the Tunica language and the neglect of many traditions. Dispersion of tribal members and the necessity to leave the reservation for work resulted in an abandonment of traditional ways and adoption of non-Indian customs. Assimilation certainly took its toll on what was once a large and thriving society. The strength of this community weathered the tide of racism, change, and cultural evolution. The tenacity of the Tunica-Biloxi did not allow total annihilation of language, religion, or tradition. Their culture lives on in its members and the memories of elders of all tribal factions: sometimes in bits and pieces, and sometimes in the minute threads of every day existence.

After a period of political dormancy, Chief Joseph Alcide Pierite took up the activist torch in the late 1960’s. He helped organize a pan-tribal organization similar to those in other regions of the United States and brought the Tunica-Biloxi question to the national stage. Indian activism gained widespread attention in the 1970’s throughout the country and provided the political boost needed to get the Tunica-Biloxi federal recognition. Chairman Earl J. Barbry, Sr., completed the cycle begun by his grandfather ushering his people into a new era of political sovereignty and economic stability with federal recognition in 1981.

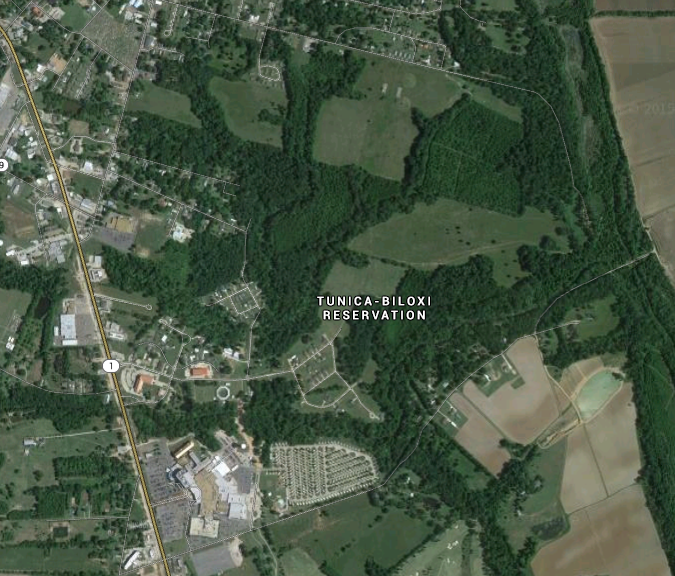

Avoyelles Parish was among the poorest in Louisiana, with an unemployment rate higher than the state and national averages. When the Tunica-Biloxi opened Grand Casino Avoyelles (now Paragon Casino Resort) in June 1994, they triggered a multi-million dollar infusion of cash that profoundly transformed the local economy. Tribal investments have created new jobs, promoted a higher standard of living, increased tourism, and breathed new life into the economic development of the region.

Tunica in the 21st Century

Cultural awareness and preservation is of paramount importance to the Tunica-Biloxi as they strive to keep in touch with the old ways. The Tunica-Biloxi Cultural and Educational Resources Center (CERC) preserves treasures from the 18th century and provides a glimpse of tribal life at that time and it impact from European contact. The CERC building is part of the Tribe’s long-range commitment to broaden the cultural, artistic, and educational offerings to its members and the surrounding communities. CERC includes a museum exhibit hall, conservation and restoration laboratory, gift shop, library, auditorium, classrooms, distance learning center, meeting rooms and tribal government offices. Traditions of crafts, music, folklore, and dance are shared at the annual inter-tribal Pow Wow and dance competition. The Language Revitalization Program has made traditional songs and stories accessible to tribal children and has reminded tribal adults of the importance of preserving a “sleeping” language. These characteristics, which identified the Tunica-Biloxi people as a cogent cultural group and community, are what keep them unified and connected to their history.

A once declining tribal nation is being restored as Tunica-Biloxi people return to their homeland and reclaim its rightful place both culturally and economically. Opportunities for employment, training, and education are bringing families back to the reservation and Avoyelles Parish. Young and educated tribal members are taking up the mantle of responsibility for business and government. They face the rigors of self-rule and daily challenges to tribal sovereignty honoring the Tunica-Biloxi motto “Cherishing our past and building for our future.”